1. INTRODUCTION

China is undergoing an unprecedented growth of economically driven rural-to- urban migration, ‘history’s largest labor flow’ (Wang and Zuo,1999, p. 276). According to the China Sixth Census in 2010, the number of migrant population had exceeded 221 million, constituting 16.5% of the total Chinese population (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2011). Due to the household registration system (popularly known as ‘Hukou’) in China which rations social benefitssuch as education, housing and medical services to every Chinese family according to their original place of registration, this large number of migrants are termed ‘floating population’, or liudong renkou in Chinese, indicating their temporary status in the cities (Solinger,1999).

Althoughthemigrantsarenotregardedasurbanresidentsandhavenoaccess to urban services, recent surveys showed that as they prolonged their stays in the cities, they gradually changed from temporary laborers to permanent settlersand brought along other family members with them, most prominently children (Duan et al., 2013). Although the scale and distribution of migrant children lacks exact measurement, it was estimated that migrant children under the age of 17 had increased to more than 35 million nationwide and about 80% of them came from rural areas (All-China Women’s Federation Report, 2013). They largely concentrated in big cities along the east coast where their parents were engaged in jobs with long working hours and low pay. In Beijing, the number of migrant children was reported to exceed 500,000, or one out of three school-age children in Beijing were migrant children (All-China Women’s Federation Report,2013).

According to the 1986 Compulsory Education Law in China, all children should go to neighborhood schools in their household registration place (Office of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Education, 2010). Because the migrant children retain the rural Hukou status in their parents’ original place of registration, no urban schools are supposed to accept them. As a result, the majority of these children could only resort to attending makeshift schools established by migrant workers or parents (dagong zidi xuexiao) in the outskirts of the city that are unstable and barely meet teaching standards, or otherwise become dropouts in cities (Han, 2004; Xie, 2013).

Since 2001, with the growing visibility of this group, the Chinese central government has issued a series of documents, popularly known as the ‘two primary responsibilities’ (liangweizhu in Chinese) policy, to facilitate the access of migrant children to urban schools. The new policy stipulated that the education of migrant children should be the primary responsibility of the destination government rather than that of the government where they migrated from, and that of the public schools rather than private schools. These policy documents also emphasized ‘equal treatment of the local students and the migrant students’ (Article 4) in terms of school participation, awards, extracurricular activities as well as tuition and fees (General Office of State Council [2003], No. 78). Changes in educational policy towards rural migrant children indicate that equal educational opportunity has become a high priority in the agenda of the Chinese top administration with its recent declaration to help the disadvantaged groups and build a harmonious society. However, as the destination city governments and public schools are called upon to shoulder major responsibilities for educating the migrant children, the current school finance scheme does not allocate them with extra funding to do so. As a result, urban schools in certain localities lack the incentives to enroll these children and continue to refuse them on various pretexts (Lei and Wang, 2012; Liu, 2007). In big cities, complicated paperwork, such as the notorious ‘five certificates’,1is usually required before migrant children can be eligible to apply for their public schools, whereas competitive schools may impose stricter regulations, extol extra fees or demand further inputs from the parents in their daily activities and school operations (Lei and Wang, 2012;Wang and Gao,2010).

Within the policy context of ‘two primary responsibilities’, the complexities involved in the urban school admission process as well as school routines continue to serve as gatekeepers that exclude their children from access to and participation in these schools. The inclusion and exclusion involved in migrant children’s schooling in the cities deserves scholarly attention. This case study, which focuses on four migrant children in a Beijing public school, aims toreveal how the localized processes of social inclusion and exclusion are enacted in the everydayinteractionsamongthemigrantchildren,theirurbanpeersandteachers. More specifically, this study seeks to address the following two research ques- tions: (1) What barriers have these migrant children experienced in access to the urban public schools? (2) Once in the public schools, to what extent are they includedinorexcludedfromtheritualsandroutinesoftheurbanschoollife?

Social exclusion and the hidden curriculum

The construct of social exclusion arose from social research on poverty and inequality and has been used by social sciences scholars to characterize the processes by which individuals or entire communities of people are system- atically blocked from rights, opportunities and resources (e.g. housing, employ- ment, healthcare, civic engagement, democratic participation and due process) that are otherwise available to members of society (Silver, 1994). Material deprivation is the most common result of this exclusion. Nevertheless, social exclusion is more than a simple economic phenomenon. Alienation, margin- alization or disenfranchisement often accompanies social exclusion. In history, individuals and communities have been excluded in many facets of social life on thebasisoftheirrace,citizenship,class,gender,personalhabitsandappearances, education, and religion. With the increased population flow within and across national borders, migrants and immigrants have become another prominent group that suffers from social exclusion because they are seen as ‘undeserving foreigners’ (Ferguson et al., 2005, p.132).

With the worldwide advocacy of civil rights after the World War II, demo- cratic governments feel obliged to promote social inclusion, the converse of social exclusion, through legitimizing affirmative actions to change institutional practices that lead to social exclusion. Social inclusion implies ‘integration into mainstream norms of access and citizenship undifferentiated by social character- istics of different populations’ (deHaan, 1998, pp. 12–13). However, in today’s world, certain populations continue to suffer from coarse or subtle forms of social exclusion. Furthermore, social exclusion in modern society relies more often than not on informal, covert mechanisms behind the policy rhetoric about inclusion.

Critical neo-Marxist scholars have used the concept of ‘hidden curriculum’in their attempts to unravel the various implicit mechanisms in the school system and the larger social environment that work towards the exclusion of the disadvantaged groups from privileges preserved for the dominantclasses(Apple, 2004; Apple and King, 1983). The hidden curriculum is classically defined as the unwritten, unofficial and often unintended lessons, values and perspectives that students learn in school. While the ‘formal’ curriculum consists of the courses, lessons, knowledge and skills that educators intentionally teachto students, the hidden curriculum consists of the unspoken academic, social and cultural messages that are communicated to students through various indirect means. How, for example, they should interact with peers, teachers and other adults, or how they should perceive different races, groups or classes of people, as well as which of their behaviors or ideas are considered acceptable or unacceptable. While not as openly acknowledged as the formal curriculum, the hidden curriculum is equally, if not more, important to students’ well-being at school. Students’ performance at school is often closely linked to whether they have mastered the complex hidden curriculum in the classroom (Giroux and Penna, 1983; Jackson,1968).

Critical scholars, thus, have been more interested in investigating school dynamics to discover those aspects of the hidden curriculum that are detrimental to equality, social justice and social integration (Apple and King, 1983; Giroux and Penna, 1983). In doing so, they link the micro-level everyday practices of schooling with the broader social structures and processes of reproduction in society at large. For example, Oakes (2005) argued that the practices of within- schooltracking,classifyingandlabelingonthebasisofrace,gender,classand/or academic achievement work to exclude certain children from full and equal participation in schooling, reflecting the power and hierarchies in the larger society. Bowles and Gintis (1976) found that the school system corresponded to social class structures in America resulting from capitalism. Students fromthe working-class families were socialized to follow teachers’ orders and memorize thelearningmaterialspassively,whichwastopreparethemtodolow-skilledand less challenging jobs in the future, whereas students from the white middle-class families received more challenging academic tasks in class that required them to engage in critical thinking and leadershipskills.

Furthermore, Bourdieu and Passeron (1990) put forward the conceptof‘cul-turalcapital’tounfoldthehiddenmechanismsthroughwhicheducationperpe-tuates prevailing hegemonic societal attitudes and legitimizes thestatusquo.AccordingtoBourdieu,socialreproductiontakesplacewhenschoolsarestruc-turedtofavorthosewhohavealreadyacquiredtheintangible‘culturalcapital’,asexhibitedinformsofknowledge,skills,language,styleandpreference,intheirfamilies (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1990). Schools tend to imposingnorms,valuesand beliefs of the dominant class as universalstandards and exert‘symbolicviolence’onthedisadvantagedgroupsthatdonotpossesstheseformsofsocialcapital,therebyreducingthesestudentstosubordinatedsocialstatusintheschools.Exposing the implicit practices, procedures, rules,relationships andstruc-tures embedded in the daily routines and instructions of the hiddencurriculumiscrucialforunderstandingthemechanismsofsocialinjusticeinschoolsettings.Thisstudyutilizestheconstructsofsocialexclusionandhiddencurriculumasits

theoretical framework to examine the actual schooling experiences of four rural migrant children in a Chinese urban school. Through a case study of the micro- level interactions, we better understand the dynamics of social inclusion and social exclusion experienced by rural migrant children in urban China.

Previous scholarship on rural migrant children in China

The emergence of migrant children in Chinese urban cities has drawn increasing attention from scholars across different disciplines, both domestic and outside China. The literature on migrant children has grown exponentially since the late 1990s. The earliest attempt was an article entitled ‘Where do floating childrengo to school?’ (Li, 1995) published by China Education daily, the most influential newspaper on education in China. Since then, the issue of rural migrant chil- dren’s education rose to the spotlight and entered into public discourse. Initial scholarly interests focused on the discussion of the Hukou system and the rural- urban dualistic social structures that deprived migrant children of their educa- tional rights in the cities (Chen, 2006; Li, 2004). Large-scale surveys were conducted at this time to obtain a general picture of migrant children’s total numbers, geographical distributions and schooling options across different regions (Duan and Zhou, 2001; Han, 2004). In a survey conducted by the Project Teamof Educational Development and Research at Chinese National Institute of Education Research (2007), about 10% of migrant children did not have schools to go to and became dropouts in cities; more than 50% of migrant children had to go to the dilapidated, self-funded schools run by migrant parents without the support of public funding at all. On the basis of these findings, scholars put forward policy analyses and recommendations about the roles and responsibilities of different levels of governments in providing education to migrant children (Lei, 2005; Liu, 2007). In the meanwhile, as the self-funded migrant schools expanded quickly and became the main schooling venue for migrant children at this time, the unsatisfactory conditions of these schools were documented and its legitimacy debated (Han, 2004; Wang, 2008; Xie, 2013). Overall, school access has been a dominant concern for migrant children in the past twodecades.

With the establishment of the ‘two primary responsibilities’ policy in 2001 and its enforcement in the following years, research attention shifted from migrant children’s school access to their schooling processes and outcomes, from macro-level structural analysis (e.g. the Hukousystem) to micro-level empirical studies, and from migrant children as a monolithic group to a range of individual migrant children’s experiences (Yu, 2008). While some scholars continued to follow up with the access issue since a large number of migrant children still faced practical obstacles in entering urban schools (Lei and Wang,2012; Yuan,2015), more studies arose to examine the educational performance, psychological health and social adaptation of migrant children in cities (Ma, 2007;WangandGao,2010).Ingeneral,theirfindingsreportedthatmigrant

children as a whole experienced loneliness, anxiety and sense of inferiority in public schools and had difficulties in school performance compared with the local peers (Li et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2009). However, these studies largely attributed the deplorable conditions of the migrant children to the lack of financial capital, social capital and/or cultural capital in migrant families (Zhou, 2008). They rarely attempted to reveal what was actually taking place within the school settings. More importantly, few existing studies delved intothe overt or covert attitudes, practices and mechanisms encountered by the migrant childreninurbanschools,whichmayleadtotheiralienationandmarginalization in schoolparticipation.

As an increasing number of rural migrant children are able to access urban public schools in recent years, a major issue becomes how the urban schools respond to their arrival and the extent to which they are included or excluded in the daily activities and routines of urban schools. This study uses a micro- ethnographic perspective to analyze the current migrant educational policy and practice by revealing the hidden mechanisms of social exclusion confronting the migrant children in their schooling processes.

2. THE STUDY: RESEARCH SITE ANDPARTICIPANTS

This study is part of a larger qualitative research project on migrant children’s identity formation in Chinese urban schools, sponsored by the Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, the Chinese Ministry of Education. Data for the study come from qualitative ethnographic fieldwork in a public school in Beijing during the past 3 years from 2009 to 2011. Beijing, the capital of China, is one of the three most popular destination cities for the migrant workers, the other two being Guangzhou and Shanghai. According to an official report, Beijing had about 7 million migrants in its ‘floating’ population in 2011, of which approximately 434,000 were migrant children aged from 6 to 14, repre- senting about one-third of the total number of children residing in Beijing (BeijingOfficeoftheSixthCensus,2011).

The present study was conducted at Dongsheng Primary School (pseudo- nym), a modest public school located in Haidian District, which was nationally well-known for its rich educational resources. Compared with acknowledged key-point2schools and university-affiliated schools concentrated in this district, Dongsheng Primary School serves a modest working-class community and also providesboardingaccommodationsforasmallpercentageofstudentsfromother parts of Beijing. The student population at Dongsheng is below 1000 and offers Grades 1–6 with four or five classrooms for each grade. When this study was conducted, there were about 40 students in each class. Not surprisingly, Dongsheng School gave priority to enrolling Beijing children and was not proactiveinreceivingmigrantchildren.However,withthedemographicchanges due to the ‘one-child policy’ in recent years, it was not able to enroll enough local children who were more interested in getting into key-point publicschools.

About half of the students in the school were Beijing urban children from the neighborhood and the other half were migrant children.

The two researchers were introduced to the school principalin 2008 by a colleague. Because the principal knew that we were education professors in a Chinese university, she expressed interest inour research project and hoped that we could offer training for the teachersabout how to do action research in classrooms. We agreed heartily. The principal assigned acoor- dinator for us, Teacher Chen (a pseudonym), Director of Teaching in the school, whose job was to facilitate us in the data collection. Withthe officially recognized role of research consultants (with no pay though), wewere able to participate in various school activities from 2009to 2012, including parents’ meetings, teachers’ meetings, extracurricular activities and open day activities. We occasionally gave lectures and provided work- shops to the school teachers.During recess time, we stayed in the teachers’ offices and had plenty of opportunities to talk withTeacher Chen and other teachersinformally.

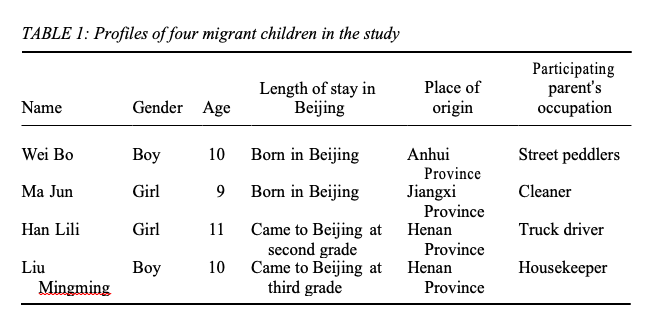

From March to December 2009, the two researchers observed all the four classrooms in the fourth grade with particular attention to the migrant children in these classes. We came to the school once a week, observing one classroom together for one month before shifting to a different classroom. Altogether we made 32 class observations. The students were quite curious about our presence and liked to chat with us in the beginning. We sat in the back of the classrooms in order not to disturb the class. As time went by, they were accustomed to seeing us around and ceased asked questions. We became quite familiar with the school routines after one semester and started to focus attention on the migrant children. We tried to sit close to them in class and talk to them after class. With the help of the head teachers, we selected four children, one from each class, to do case studies. The children’s profiles are included in Table 1 below.

Thefourchildrenwereselectedbasedontwocriteria.First,wesoughttoinclude migrantstudentsfromdifferentplacesoforiginwithdifferentpersonalandfamily characteristics for the sake of variability. Second, their parents were willing to participateinourstudy.Forthefollowing2years,2010–2011,weofferedtutoring tothesefourmigrantchildreninschoolandpaidfrequentvisitstotheirtemporary homes in Beijing. As we established close rapport with the migrant families, we conducted both formal and informal interviews with the four children and their participating parents. During the interviews, we learned about their family back- grounds,howtheyhadbeenabletoaccessDongshengSchool,thedifficultiesthey hadexperiencedatschoolandtheirexpectationsforthefuture.Later,wecontinued to do classroom observations with less frequency but engaged more in informal conversations with their head teachers and classmates about how these migrant children behaved and performed in class, how they socialized at school andwhat extracurricular activities they participated in. Altogether we conducted 22formal interviewswiththe4migrantstudents,4parentsand4headteachers.

Data analysis for qualitative research was a continuous and developmental process that was parallel with data collection. We wrote memos and discussed preliminary findings throughout the fieldwork to facilitate subsequent data col- lection and analysis. Weapplied ‘constant comparing and contrasting’ method rooted in grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) for thematic analysis ofthe data. We first coded the interview and fieldnotes, both broadly and descriptively across all the data. In some cases, we attached more than one code to a single paragraph. After the primary coding, we continued to read through the data to refine and standardize the codes in order to find possible themes (Denzin and Lincoln, 1998). Similar events, activities, beliefs and experiences were grouped together under one theme. By doing this, the data was reduced to a smallnumber of codes that represented larger themes. We then organized and interpreted the themes in analytical and logical ways to permit the drawing of possible conclu- sions and hypothesis. The tentative conclusions were then triangulated and checked against more data from the ongoing participant observations and infor- mal talks in thefieldwork.

There are several obvious limitations with this approach. The strengths of prolonged ethnographic fieldwork come from the depth and richness of the data obtained. However, the case study approach focusing on only four migrant children inevitably leads to the limited generalizability of the study. Thus, in presenting the findings below, we take caution to avoid over-generalization and engage more in ‘thick descriptions’ (Maxwell, 1996).

3. DISCUSSION

Gate-keeping: niches for migrant children

Even though the ‘two primary responsibilities’ policy at the national level has established the principle of equal treatment to the migrant children in terms of

school access and daily participation, many migrant children in Beijing, as in other provinces and municipalities, are not accepted by public schools because the ‘five certificates’ as required by the local education commission are simply insurmountable obstacles (Lei and Wang, 2012). For example, a large number of migrant workers are unable to secure a working contract or rent contract with their employers or landowners because they are typically engaged in unstable occupations and stay in cheap basements or flats that are not meant to be subleased. More importantly, some of their children might not qualify for the ‘single child’ criteria since rural migrant families usually have more than one child, a permissible and widespread practice in rural China.

The four children in our study, however, were fortunate enough to have parents who had successfully obtained the five documents on their behalf. Nonetheless, each of them told a story about how they went through the bumpyroadtogetintoDengshengSchool.

Han Lili: I had to take a test before I could come to this school. It was terrible! I hadn’t learned the stuff in my home village. But they finally accepted me after my mother promised that I would work extremely hard to catchup.

Lili finished the second grade in her rural school and then transferred to Dongsheng School. Since the interview teacher regarded her as falling behind, she had to repeat the second grade at Dongsheng instead of progressing into the third grade.

Ma Jun was a migrant girl that stood out among the four students in the case study because she was the only student with academic potentials upon entry to school. She was born in Beijing and ‘liked to read books since childhood’ (Ma Jun’sMother).Althoughherparentscouldnotaffordtosendhertoanypre-school in Beijing, she ‘had learned many things from her older sister’ beforeschool-age, whichhelpedhergetintoDongshengSchoolandalsosavedmoneyforherfamily.

Teacher Chen: I remember Ma Jun because she was a very smart girl. She was quick in answering the questions I asked in the interview. But ourschoolchargedextrafeestonon-localstudentsthatyear.Ma Jun’s mother didn’t want to pay. Later I called her and said she didn’tneedtopaytheextrafee.MaJunisinourschoolnow.

Wei Bo was regarded as a ‘problem’ boy by his teachers even though he was born in Beijing. His parents sold fruit on the street across Dongsheng School from morning till night, so Wei Bo grew up on the street and was quite familiar with the neighborhood. But he was described as being ‘slow’ and seemed not ‘understanding the questions [teachers]asked’ (Teacher Chen). His head teacher also believed there was something wrong with Wei Bo’s verbal abilities: ‘Once his mother told me that he didn’t speak until three years old. I guess maybe his

parentswerebusysellingfruitsandnobodywastheretotalktohimwhenhewas a baby.’ Wei Bo was initially rejected by Dongsheng School, but his fate was changedbyanewreformintroducedattheschoollaterthatyear.

Wei Bo’s Mother: They started a Peking Opera Club and were recruiting chil- dren to learn Peking Opera after class every day. They asked us if Wei Bo could join the Club. I said yes, so he could go to school. By the second grade, he quit because he was not really good at it.

Liu Mingming’s enrollment at Dongsheng School was purely coincidental. His parents worked as decorators and didn’t bring him to Beijing until he was in the fourth grade. His parents didn’t know which school to send him to, so Liu Mingming idled away at home for two months. Later on, his father did decora- tion work for a client who happened to be a teacher at Dongsheng School. With the teacher’s help, Liu Mingming’s father learned about the application proce- dures and successfully enrolled him into Dongsheng. During the interview, Liu Mingming’s father talked about the importance of ‘personal connections’, widely known as ‘guanxi’ in Chinese, in securing a school seat for his child.

Liu Mingming’s Father: I didn’t know which school Liu Mingming should go

to in the beginning. But then when I chatted with my client, he said he was a school teacher. Can you imagine? The Beijing native people have the informa- tion I need. Without his help, I wouldn’t know which schooltoapplyforandtheschoolmightnotwanthim. We didn’t pay any extra fees because of theteacher.

While school enrollment for the Beijing local children generally follows a ‘first-come-first-serve’ procedure, migrant children have to face gatekeepers set up by individual schools, the most common ones being academic performance and/or financial charges. As it turns out, many migrant students are rejected on the justifiable pretext that they lack academic preparation and will not be able to function in urban schools. As Teacher Chen explained,

Teacher Chen: Now the society pays a lot of attention to the rural migrant children. They are pitiful because their parents can’t provide good conditions for them. The society has to be kind to them. So they are allowed to study in city schools. But some rural children indeed have zero preparation for school. Schools are not philanthropic institutions. We are subject to a lot of pres- sures. If students’ academic performance waters [our school’s overall performance] down, we will be criticized as not doing a good job.

Here the important message is that urban schools accept the migrant children not because they have to, but because they want to be kind and merciful. ‘Equal treatment’ is seen as a favor to the migrant students rather than as their inherent rights since they are, after all, ‘outsiders’ to the urban school system. As ‘schools are not philanthropic institutions’, it is up to the individual schools to decide whom they accept or reject. Thus, the migrant students either have to be academically excellent or be ‘useful’ to the school in other ways, such as knowing someone in the school, as in Liu Mingming’s case; repeating a grade, as in Han Lili’s situation; or fitting into in a special program that are recruiting students, as Wei Bodid.

In-class participations: equal treatment under the same curriculum?

When speaking of the migrant students, the teachers reported proudly that they treatedthemequally,thatis,thesameastheBeijinglocalstudents.However,the time-honored question is whether the equal treatment among those with unequal status results in differentialexperience.

Head Teacher 4: We don’t discriminate against any student, whether they are localorfromoutsideBeijing.Welookateachindividualchild and judge them based on their school performance and beha- vior. We don’t look at their parents’ background. We don’t carewhoisaruralmigrantchild.

Indeed, in the fieldwork, we found no distinction between the migrant children and local children in the school routines and daily activities. Students rarely talked about their family incomes or occupations, except for close friends. The identities of migrant children were obscured in the unan- imous school requirements for everybody. Students wore uniforms at school and used the same textbooks. There was no ability grouping or tracking in the teaching of any subject. They were even distributed with the same lunchbox prepared by the school cafeteria. As one Beijing student said: ‘They don’t seem different from us. We play together. I don’t even know who doesn’t have a BeijingHukou.’

The apparent non-distinction may probably lie in the fact that the Beijing local students attending Dongsheng School had rather modest family back- grounds as well. However, when it came to academic performance, the teachers openly admitted that the migrant children in general were low- performing, with the transfer students from rural schools struggling the most in class. Although they had professed that they did not label students according to their Hukou status, the teachers nonetheless attributed the migrant students’ low performance to their family circumstances without hesitation.

Head Teacher 3: The migrant families are not necessarily low income. Some of them do small businesses and make more money. But they don’t care about their children’s education.

Head Teacher 2: Family is very important in one’s education. You see, Wei Bo never does homework. His mother seldom comes to the parents’ meeting even though she sells fruit across the street every day. She doesn’t pay any attention to her son’s study. I said to her once: Which is more important, selling fruit or your son’s education?

According to these teachers at Dongsheng School, urban parents attachedgreater importance to children’s education than migrant parents, who tended toconcentrate all their time and energy on making money in order to survive in thecity. The lack of parental supervision and guidance was regarded as an importantdisadvantage leading to migrant children’s low performance in academic work.English was reported to be the most challenging subject to the majority ofmigrant children. In our observations of the English classes at DongshengSchool, we found many Beijing students spoke fluent English with close tonative accent. One of the classes talked about Thanksgiving and what Americanpeople would do on this holiday. The teacher used a considerable amount ofEnglish in her instruction and organized student activities. The local studentswere very active in the whole process, but the migrant children remained silentand were virtually excluded from such discussions. As a Beijing local studentlater explained, ‘We go to Pop English class at New Oriental School. They teachus more advanced English, sometimes by an American teacher, because ourtextbook is too easy.’ It was a common practice for urban parents in China tosend their children to the paid supplementary classes after school, the so-called‘shadow education’ (Bray, 2009). Obviously, most migrant children did notattend these after-school programs either because their parents could not affordthem or because they had not realized the importance of training classes outside

school.

With the clear distinction between the two groups of students in academic achievement, most teachers seemed to have accepted the fact that migrant children tended to be low-performers and, therefore, had low expectations for them. It was especially revealing to us that Ma Jun, the high performing student in the beginning, seemed to have lost her advantage by the fifth grade and was described by her head teacher as ‘medium level’ and ‘exceptional only in the Chinese subject’.

Ma Jun’s Head Teacher: Yes, she is hardworking as usual. But as they move tohigher grades, memorization no longer guarantees good test scores. The new curriculum emphasizes students’ critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Ma Jun’s mother pays attention to her daughter’sstudy, but their family doesn’t have a computer. Some assignmentsrequireindependentresearchontheinter- net. She simply skipped thoseassignments.

Ironically, the new curriculum reform launched in 2001 that aimed to rescue the Chinese students from dull drills and rote memorization worked negatively on the migrant children and led to a huge divide between the migrant and urban children. Under the disguise of ‘equal treatment’, Dongsheng School did not provide any remedial programs or tutoring to help the migrant children adjust to the new curriculum and innovative teaching methods. The migrant parents, for their part, did not understand the new curriculum and were confounded by teachers’ assignments.

Liu Mingming’s Mother: The Beijing school is not like our rural school backhome. The teachers often assign strange assignments or ask them to find answers by themselves. We don’t know what the teacher wants.

As a result, the migrant children were left to themselves in the classes, struggling with academic work and feeling marginalized. Even though they had obtained the opportunity to study in the same classrooms with their urban peers, they felt out of place in class and were not able to comprehend thecontent materialsthatwereclearlyorientedtowardstheurbanlifeinthemetropolitancity of Beijing. In contrast, the urban children appeared smart and knew exactlywhat the teachers wanted. Parental supervision at home, family-school partnership, supplementary classes and the new curriculum requirements together constituted the ‘hidden curriculum’ in the urban schools, which remained elusive to the migrant children and led to their schoolfailure.

Peer interactions and extracurricular activities: an invisible wall

Schools are not just places for learning academic knowledge, but are also important settings for socialization and peer interactions. Students interact in class under the supervision of the teachers. During recess time, they interact more freely and play with friends. At Dongsheng School, as typically in Chinese urban schools, students have 10 minutes’ recess time between each class period. After two classes in the morning, students line up on the playground to do gymnastics, followed by half an hour’s free time. After lunch, they have one hour’s recess before the afternoon classes started. While the migrant children in our study were quite passive in class, they were excited and active during the recess. They intermingled with the local students and played games together. However, when asked who their best friends were, they usually referred to migrant classmates. Conversely, Beijing local students very rarely identified migrant children, even though they were not clearly aware of their Hukoustatus.

Ma Jun: Xiao is my best friend because we go home together every day. We live very close. We get along. That’s why we become good friends.

Meng (Beijing girl): Good students are usually friends. Who wants to be friends with badstudents?

Zhao (Beijing boy): My best friend is Li Xiang. We are both in the Peking OperaClub.

In the fieldwork, we found three factors vital to peer interactions at Dongsheng School: (1) living geographically close, (2) participating in com- mon extracurricular activities and (3) achieving desirable academic perfor- mance. None of the students mentioned family background in friend-making, but migrant children were distinct in each of the above three dimensions. First of all, they were not likely to live close to Beijing local students since migrant families usually rented cheap flats or basements in a dilapidated neighborhood to lower the cost. As a general pattern, migrant children tended to become friends with those living in close proximity and from similar family background.

Secondly, extracurricular activities at school are important channels for friend-making. As children participate in common extracurricular activities, they develop team spirits and have more opportunities to contact and become friends. The extracurricular activities at Dongsheng School included after- school programs from Monday to Thursday, occasional field trips, Peking Opera Club and the annual Sports Meet. However, migrant children were often excluded from most of the extracurricular activities at school because their parents either could not afford these activities or have no interest or time to getinvolved.

Wei Bo’s Mother: He said he wants to join the Kung Fu class. I think it’suseless, just wasting money away, but he insisted. So we paid 200 yuan a month for his Kung Fu class, but soon he quit.

In China, many after-school programs charge fees that migrant families with little income are reluctant to pay. Parental participation is also important in certain extracurricular activities, such as field trips and holiday celebrations. As the migrant parents typically work long hours, they are usually unable to get involved in children’s school activities.

Wei Bo’s Head Teacher: Beijing parents are very supportive of theirchildren’sschool activities. They help organize and prepare. But those migrant worker- parents don’t even attend par- ents’ meeting once a year! When I called them, they saidtheywouldcome.Butthentheydidn’tshowup.

Thirdly, as we have demonstrated in the previous section, the migrant children usually perform at the lower end of academic achievement. At Dongsheng School, the students seemed to be very clear about who were academically ‘good’ since teachers often praised the high-performing students openly and recommended them to participate in school-wide contests. The low- performing students’ lack of success was also made visible through frequent test score rankings.

Zhu (Beijing girl): He always fails in the tests. We call him ‘Liu Mingming Valley’ because his score never climbs up. Nobody likes to pair up with himin group activity. He is always the last, even in the P.E. class.

In Chinese schools, students’ test scores are not kept private, but are often disclosed to everyone in class through rankings. At Dongsheng School, students of Grade Four were tested every month on Chinese, math and English. In addition, there was a final test on these three subjects at the end of each semester. Students were routinely ranked after each test, and their rankings were made public through various visual means, such as graphs or flags on the wall showing each student’s achievement. As other students in the class climbed up the achievement axis as the semester progressed, Liu Mingming’s name stayed at the bottom. The gap was so big that it earned Liu Mingming the nickname of ‘Valley’. While the rankings were to encourage students to work hard and compete with one another, the low-performing migrant children didn’t benefit from them, but were made a laughing stock instead.

Due to the three factors mentioned above, the migrant children are clearly hindered from participating fully inschool activities and interacting with their urban peers both in school and out of school. Although placed in the urban school, they possess neither financial capital to get involved in the extracurricular activities and supplementary training classes nor cultural capital manifested in parental involvement or academic excellence towin friendshipand respect. As a consequence,such ‘hidden curriculum’, whichis equally crucial to one’s school life as the formal curriculum, makes up an invisible wall between the migrant students and Beijing local students, leadingto de facto segregation in their behavior patterns and school experiences.

4. CONCLUSION: FROM POLICY TOPRACTICE

Whereas previous studies generally attributed social injustice with regard to migrant children’s schooling to the macro-level institutional barriers (Li, 2004; Lei and Wang, 2012), such as the Hukou system, or to the disadvantaged social status of migrant families (Zhou, 2008), this study sought to investigate the

hidden mechanisms in the urban school practices that may have led to the social exclusion and marginalization of migrant children. Based on prolonged ethno- graphic fieldwork in a Beijing public school, this study found that even though ‘the two primary responsibilities’ policy has allowed rural migrant children to attend urban public schools, migrant children continue to be excluded from school access and school participation in the cities. Three key aspects of exclu- sions were revealed: access to school, in-class participations and peer interac- tions. In terms of access, migrant students not only have to obtain the ‘five documents’ to enroll in urban schools, but also have to find appropriate niches in order to be accepted by the public schools, such as good academic performance, knowing somebody in the school or fitting into a particular school program. The rationale behind the selective admission of migrant children is local educators’ attitudes towards migrant children as outsiders whom they show sympathy for but are not obligated to educate.

Once enrolled in public schools, the migrant children coming from rural family background with weak academic foundations/preparations oftenhave difficulty in study and are not familiar with the teaching materials. However, given the ‘equal treatment’ principle, urban schools adopt the mainstreaming practice without providing tutoring or remedial programs to help the migrant childrencatchup.Moreover,thenewcurriculumreformlaunchedinrecentyears in urban schools, with its emphasis on innovative teaching methods and urban- oriented contents, puts the migrant students at a further disadvantage in aca- demics. In turn, low academic performance and little involvement in paid extra- curricular activities prevent the migrant children from networking with the Beijing local students and subjugate them to discrimination and ostracism from their urbanpeers.

At first glance, the emphasis on academic achievement seems to lie at the root of the three aspects of exclusions. However, upon closer examination, we found that academic performance is not simply a matter of how much effort individual students put to study, but hinges upon a number of complicated factors, such as one’s family background, parents’ inputs to children’s school work, teachers’ expectations, available learning opportunities, appropriate teach- ing methods, and participation in extracurricular activities or supplementary classes in and outside school. All of these constitute the ‘hidden curriculum’ in the Chinese urban school settings that works against the migrant children and leads to their marginalization and exclusion in school access, in-class participa- tions and peer relations.

Although discourses of inclusion and equity permeate government policy documents, our ethnographic fieldwork on the everyday life of migrant children in a Beijing public school suggests that the emphasis on ‘equal treatment’ is only superficial and fails to take into account of the migrant children’s dis- advantaged status and special educational needs. Under the disguise of ‘equal treatment’, migrant children are subject to learning in a swim-or-sink way and tend to be excluded in many aspects of urban school life. To translatethe

policies into reality and bring about true integration of rural migrant children in urban schooling, it is important for the Chinese urban schools and educators to consider poignant questions related to the basic educational rights of migrant children in school access and participation. They also need to engage with the hidden curriculum embedded in the everyday school practice, which reflects the power and hierarchies in the large society and rationalizes exclusionary treatment towards the migrant children. At the very least, the urban teachers should provide supplementary help to the migrant children before they insist upon academic performance as the criteria for allocating school resources and opportunities.

5. DISCLOSURESTATEMENT

Nopotentialconflictofinterestwasreportedbytheauthors.

6. FUNDING

This study was funded by two research grants: ‘Education of Migrant Children in Urban China from the Perspective of Balanced Social Development (shehui junheng fazhan shijiao xia chengshi liudong ertong jiaoyu wenti yanjiu)’sponsored by the Chinese National Social Sciences Foundation (Project No.: CHA100145) and ‘Identity Formation of Chinese Migrant Children in Urban Cities (chengshi liudong ertong de ziwo shenfen jiangou yanjiu)’ sponsored by the Humanities and Social Sciences Division of the Ministry of Education in China (Project No. 09YJC880100). Writing of the article was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Funds of Renmin University of China (Project No. 10XNK126).

7. NOTES

1 Five certificates refer to parents’ temporary residential certificate, rent contract to show their actual place of residence in the city, parents’employment contract, proof of no caretakers available back home, and single child certificate.

2 Key-point schools are those schools acknowledged by Beijing Municipal Education Commission as high-quality schools in the district. Dongsheng School is not one of them.

8. REFERENCES

All-China Women’s Federation Report (2013, May 11) Research Report on RuralMigrant Children and Left-Behind Children (liushou ertong he chengxiang liudong ertongyanjiubaogao),ChinaEducationDaily(zhongguojiaoyubao).

Apple, M. and King, N. (1983) What do schools teach? In H. Giroux and D. Purpel (Eds) The Hidden Curriculum and Moral Education (Berkeley, CA, McCutchan Publishing Corporation), 82–99.

Apple, M. W. (2004) Ideology and Curriculum (25th Anniversary) (New York, Routledge).

BeijingOfficeoftheSixthCensus(2011)Ananalysisofschool-agechildrenfromoutside Beijing: The Sixth National Census Data. Available at: http://news.ifeng.com/mainland/detail_2011_08/17/8459554_0.shtml

Bourdieu, P. and Passeron, J. C. (1990) Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture

(2nd edn) (London, Sage Publications).

Bowles, S. and Gintis, H. (1976) Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life (New York, Basic Books).

Bray,T.M.(2009)ConfrontingtheShadowEducationSystem:WhatGovernmentPolicies forWhatPrivateTutoring?(Paris,UnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCultural Organization, International Institute for EducationalPlanning).

Chen, J. (2006) China’s household registration system reform and rural-urban population flow (zhongguo huji zhidu gaige he chengxiang renkou qianyi). In F. Cai and N. Bai (Eds)TheLaborFlowinChina’sTransformationPeriod(zhongguozhuanguishiqide laodongliliudong)(Beijing,SocialSciencesLiteraturePress).

deHaan, A. (1998) Social exclusion in policy and research: operationalizing the concept. In J. B. Figueiredo and A. de Haan (Eds) Social Exclusion: An Iloperspective (Geneva, ILO), 11–24.

Denzin, N. K. and Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds) (1998) Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials (Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications).

Duan, C., Lv, L. and Zou, X. (2013) Major challenges for China’s floating population and policy suggestions: an analysis of the 2010 population Census data (dangqian woguo liudong renkou mianlin de zhuyao wenti he duice), Population Research (renkou yanjiu), 37 (2), 17–24.

Duan, C. and Zhou, H. (2001) An analysis on the status of migrant children and youth in Beijing (beijingshi liudong ertong shaonian zhuangkuang fenxi), Population and Economy (renkou yu jingji), 1, 5–11.

Ferguson, I., Lavalette, M. and Whitmore, E. (2005) Globalization, Global Justice and Social Work (London and New York, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group).

Giroux, H. and Penna, A. (1983) Social education in the classroom: the dynamics of the hidden curriculum. In H. Giroux and D. Purpel (Eds) The Hidden Curriculum and Moral Education (Berkeley, CA, McCutchan Publishing Corporation), 100–121.

Glaser, B. and Strauss, A. (1967) The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research (Chicago, Aldine).

Han,J.(2004)Surveyreportonthestateofcompulsoryeducationamongmigrantchildren inBeijing,ChineseEducationandSociety,37(5),29–55.

Jackson, P. W. (1968) Life in Classrooms (New York, Holt, Rinehart & Winston).

Lei, W. (2005) Policy alternatives for migrant children’s education: a perspective of multiple demands (cong duoyuan xuqiu kan liudong ertong jiaoyu zhengce xuanze), JournalofCentralChinaNormalUniversity,HumanitiesandSocialSciencesEdition (huazhongshifandaxuexuebao,renwenshehuikexueban),3,12–16.

Lei, W. and Wang, C. (2012) On the legitimacy of school access gatekeepers for rural migrant children (nongmingong suiqian zinv ruxue menkan de helixing yanjiu), Research in Educational Development (jiaoyu fazhan yanjiu), 10, 7–13.

Li, J. (1995, January 21) Where do floating children go to school? An exploration ofrural migrant children’s education (liudong de haizi nar shangxue—liudong renkou zinv jiaoyutantao).ChinaEducationDaily(zhongguojiaoyubao).

Li, Q. (2004) Rural Migrant Workers and Social Stratification in China (nongmingong yuzhongguo shehui fenceng) (Beijing, Social Science Archives Press (sheke dangan chubanshe).

Li, X., Zou, H., Wang, R. and Dou, D. (2008) A correlation study of the self-esteem development characteristics, academic performance and teacher-student relationship among migrant children in Beijing (beijingshi liudong ertong zizun de fazhan tedian jiqi xueye xingwei shisheng guanxi de xiangguan yanjiu), Psychological Sciences (xinli kexue), 4, 909–913.

Lin, X., Wang, X., Zhang, M. and Zhou, J. (2009) Factors influencing the academic performance of migrant children (liudong ertong xueye biaoxian de yingxiang yinsu), Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Sciences Edition) (beijing shifan daxue xuebao shehui kexue ban), 5, 41–47.

Liu, C. (2007) Between the central and provincial governments: the operationalization of migrant children’s educational policy (zai zhongyang yu difang zhijian-mingong zinv jiaoyu zhengce de caozuohua), Youth Studies (qingnian yanjiu), 10, 24–28.

Ma, L. (2007) Survey analysis on migrant children’s school education, Educational Development and Research (jiaoyu fazhan yanjiu), 3, 56–61.

Maxwell, J. (1996) Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach (Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage).

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2011). Gazetteon major figures of the 1% Sampling of the 2010 Population Census (2010 nianquanguo 1% renkouchouyang- diaochazhuyaoshujugongbao). Available at: http://www.stats. gov. cn/tjgb/rkpcgb/ qgrkpcgb/t20110428_402722232html

Oakes, J. (2005) Keeping Track: How Schools Structure Inequality (2nd edn) (New Haven, CT, Yale University).

Office of Legal Affairs, Ministry of Education (2010) A Compilation of Education Laws,Policies, and Regulations in People’s Republic of China. (zhonghuarenmingonghe-guojiaoyufalvfaguiguizhanghuibian)(Shanghai, East China Normal University Press).Project Team of Educational Development and Research at Chinese National Institute ofEducational Research (2007) Compulsory education for rural migrant workers’chil-dren in China (zhongguo jincheng wugong jiuye nongmin zinv yiwu jiaoyu yanjiu),

JournalofCentralChinaNormalUniversity,HumanitiesandSocialSciencesEdition (huazhongshifandaxuexuebao,renwenshehuikexueban),2,129–134.

Silver,H.(1994)Socialexclusionandsocialsolidarity,InternationalLabourReview,133, 531–578.

Solinger, D. J. (1999) Contesting Citizenship in Urban China: Peasant Migrants, the State, and the Logic of the Market (Berkeley, CA, University of California Press).

Wang, F. and Zuo, X. (1999) History’s largest labor flow: understanding China’s rural migration, The American Economic Review, 89 (2), 276–280. doi:10.1257/aer.89.2.276

Wang, L. (2008) The marginality of migrant children in the urban Chinese educational system, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29 (6), 691–703. doi:10.1080/01425690802423361

Wang, Y. and Gao, Y. (2010) Social Integration between the Migrant Peasants’ Children and Urban Citizens (liudong ertong yu chengshi shehui ronghe) (Beijing, Social Sciences Academic Press (shehui kexue wenxian chubanshe)).

Xie, B. (2013) The impact of urbanization on migrant children’s schooling options (chengshihua jinchengzhong liudong renkou suiqian ziv yiwu jiaoyu wenti yanjiu), Beijing Social Sciences (Beijing shehui kexue), 1, 21–25.

Yu, Z. (2008) From the margin to the center: review of migrant children’s education researchinthepasttenyears(congbianyuandaozhongxin:shinianlailiudongertong jiaoyuyanjiudelicehng),EducationalGuide(jiaoyudaokan),3,13–15.

Yuan, G. (2015) An interpretation of the ‘two primary responsibilities’ policy, Journal of Chinese Agricultural University, Social Sciences Edition (zhongguo nongye daxue xuebao, shehui kexue ban), 1, 51–54.

Zhou, H. (2008) Strategies to promote the educational equity of migrant children: the perspective of cultural capital (lun liudong ertong jiaoyu gongpinghua de celve— wenhua ziben de shijiao), Educational Theory and Practice (jiaoyu lilun yu shijian), 9, 23–26.